|

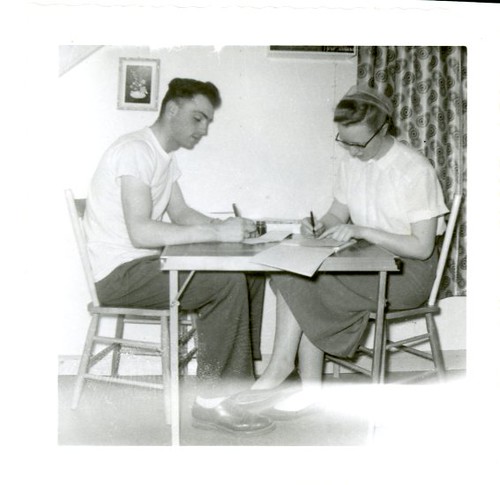

| (click through to image source) |

The world, and indeed the classroom, does not evolve around me.

Pretty simple concept to grasp, right? Yes in theory, but in practice, it's a topic that comes up often in my highs and lows.

I have been known to tout the wisdom "your worst qualities are your best qualities and vice versa," but never has it been so clear in my own reflections as this past round of TIP recording. My highs and my lows both tend to originate with my accepting the old adage, "it's not about me."

When I make it

not about me in the classroom, the level of engagement and authentic learning increases tremendously. This is something my coach brought to my attention when she visited my class and observed me teaching French through repetition, then through a book project where the words they could include in the book had already been chosen for them... by me. She challenged me to think about the questions we hear in our Language and Literacy class on a regular basis: Whose voice is being heard? Whose words/questions are being honored?

This has become my mantra as I seek to revolutionize my approach to instruction. In my mind I am constantly asking myself "are their questions honored? Are their words honored?" as I design curriculum and engagement activities to promote student-centered and critical learning practices.

My first step in the right direction came from a frightening event where me, our science teacher, and a group of 6 kids got attacked by a swarm of yellow jackets while measuring the trees in the audobon next to the school. (Read my attempt to turn horror to humor in my blog post about the experience

here). Understandably, kids had a lot of thoughts and questions about this traumatizing event, which I took as a message from them that this was a topic they were thirsty to know more about. In my growing flexibility and ability to toss out teacher-centered plans in favor of student-driven new directions, I encouraged these questions and left them open ended, because as Strieb taught me, “Naming often closes off discussion because, for some people, once you name something, there may be nothing more to say about it” (Cochran-Smith and Lytle, 1993, p.126). In my goal to have a classroom that puts more energy into honoring student inquiry rather than teacher directives, I let their questions be, and instead invited the class to create a KWHL chart (Know, Want to know, How to learn, Learned). I laid out the chart on a large piece of chart paper and invited students to write what they "know" about yellow jackets and what they want to know about yellow jackets on sticky notes to stick into the appropriate column. We then came together and discussed what we knew, what we wanted to know, and how we would go about finding our answers. Sure, a perfectly fine lesson planned around

The Paper Bag Princess got tossed out the window, but as I am constantly reminding myself: It's not about me or my beautifully planned lesson. In this moment in time, they didn't care about the Paper Bag princess, they cared about their healing stings and their newfound phobia of the outdoors, and getting to the bottom of why this experience occurred. For the next few weeks, it informed both their engagement in informational text, as well as the topics of their creative writing, like in this delightful poem by one of my 2nd graders:

Riding on the high of this successful student-centered inquiry moment, I dove head first back into my Language and Technology class, taking with me my expanding edges in facilitating a student-driven learning experience. I abandoned the "j'aime" books that only showcased MY words, and instead invited students to choose a country to study in honor of UN Day. For half of the students, the engagement I designed was perfect, and they were able to pick out facts from a kid-friendly article about the UN and collaboratively record and report them with their partner. For the other half of the class (the younger half), I quickly realized I should have differentiated a lot more for their developing literacy needs. The younger students were somewhat overwhelmed by the open-ended nature of the task with minimal teacher directives, causing interest to wane, which is where scaffolding would have come into play. A quick revisit to Flint reminded me that “when teachers provide appropriate scaffolding to struggling readers and writers, they create a learning environment that presents challenges in a supportive context; provides security through successful risk taking on a daily basis; and includes opportunities for students to begin assuming responsibility for their learning” (Flint, 2008, p.364). Of course in my development as a teacher-guide, I want my students to be successful risk takers, take on challenges, and assume more responsibility as critical thinkers and knowledge seekers, but some of them needed more support in reaching these goals. Undaunted, I went back to the drawing board and created a graphic organizer with some starting off points and some spaces for student inquiries to be inserted. The project is open-ended, in that if one aspect of their research captures their imagination, they are free to pursue that topic as the focal point of their project.

For example, this student who chose to study China quickly got through the initial questions and even her own question about Chinese holidays, which led her towards something that truly piqued her interest, the Dragon Boat Festival.

We followed this up with a trip to the library, where as much as possible students used the library resources independently to locate books on their topic of choice. Chloe quickly found a whole section on Dragon Boat festival and immediately began devouring the books right there on the floor between the stacks. Would this have been the case if I had told her "Chloe, you are assigned Canada and you need to find out the population, their currency, and name one historical Canadian figure"? Just like Buhrow and Upczak Garcia state in

Ladybugs, Tornadoes, and Swirling Galaxies, my goal "is to make an academic environment where all inquiries are valued and kids have the dispositions or the attitudes and inclination to work independently" (Buhrow and Upczak Garcia, 2006, L. 540). I believe my growth in becoming a guide who facilitates rather than "the one who has the knowledge" is allowing my class to evolve in this direction.

Again and again I am reminded by these student-driven engagements full of energy and enthusiasm that

it's not about me. And the more I make it

not about me the more authentic and alive the learning in the classroom becomes, despite my growing pains in scaffolding as I push these edges of mine.

The same mantra can be applied to my reoccurring lows, which often focus on the challenging behavior of particular students. As I examined my highs and lows across the month, a pattern began to emerge in the way I deal (unfruitfully) with these challenging behavioral moments. On more than one occasion I recorded a feeling of guilt and remorse after using a sarcastic tone with students. In

Conscious Discipline, Bailey discusses the role trigger thoughts play in a teacher's response to a challenging situation. In the self assessment found on page 31, I learned that my most engaged in form of trigger thoughts is “magnification” (Bailey, 2000, p.31); indeed, I checked every single box in that category. I've been reflecting on this, and I think my tendency to magnify a situation into something "I can't stand" or is "intolerable" leads me to try to lighten the stress by turning to humor, or rather to my preferred brand of humor, sarcasm. While indulging in magnification, I sometimes feel like I will burst if I don’t release my mounting tension, but the truth is, sarcasm relieves my tension by taking it out on the kids. I am working to remind myself that I have choices and I am in control of my reactions to stress. I don’t HAVE to use sarcasm and furthermore, I CAN stand the situation. In fact, I'd argue that it's my job to stand the situation, and to exercise self control. As Bailey reminds me, “Self control is an act of love and a moment-by-moment choice” (Bailey, 2000, p.34). There are better ways to cope with frustration than sarcasm. This becomes even more vital in consideration of Wood's assertion that “teasing, joking, and especially sarcasm are painful to the seven-year-old” (Wood, 2007, p.88). Of course the last thing I want to do is inflict emotional pain with my words or demeanor, and doing so completely undermines the work I do to model friendship skills and kindness. What's more, sarcasm makes it about

me and making

me feel better, and causes me to lose grasp of the opportunity to turn the moment into a teachable one.

It's not about me, but it's not NOT about me either. It's about that balance between myself and my students, where we share in the responsibility of their learning. I think I am getting closer to becoming that problem-posing educator who advocates with students and supports them in owning their own learning. He describes such a teacher quite eloquently when he says, "the problem-posing educator constantly re-forms his reflections in the reflection of the students. The students—no longer docile listeners—are now critical co-investigators in dialogue with the teacher” (Freire, 1970, p.81). My job now is to become an expert on scaffolding, so that co-investigation is possible for ALL students, and they are given just the right amount of autonomy balanced with a guiding structure. This plays into my longstanding goal of becoming a better more efficient planner, as scaffoldng well requires knowing several steps into the future and having well assembled plans. I have a feeling this balance will be a lifelong study.

Lastly, I absolutely must share my all time favorite Freire quote (okay so we've only read two chapters, but my favorite SO FAR): “The teacher is no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow” (Freire, 1970, p.80).

This quote holds special significance for me as a literal student of teaching. I am so grateful to my students, some of whom have been with me for 3 years now, and the patience and grace in which they tolerate my learning curve as I learn to become a better teacher. Perhaps then, my mantra should not be "it's not about me" but rather, "it's not

just about me." Because in many ways, this teaching journey

IS about me: it's my career and my life's calling after all; but it's about me in collaboration with them, and that collaboration is what I am discovering teaching to really be about the more I read, study, and experience with my little teachers.

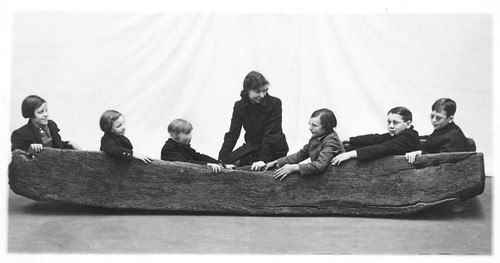

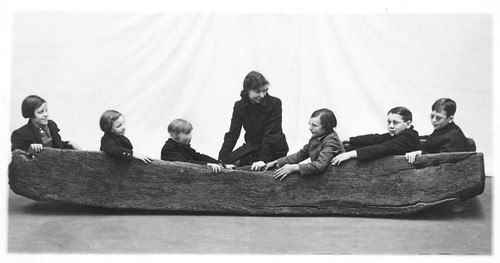

It's not just about me. We're all in this boat together.

|

| (click through to image source) |